THE MESSENGER

The messenger came from the north, from the capital of the Empire. He bore all the hallmarks of a boring career bureaucrat. Lines of age reached out from his deep-set eyes, and grey lined his hair. His shoulders hunched as though they yearned to join with his ears. Though it was plain to everyone from the way he squinted, he would never admit that his eyesight was failing.

But he was not an ordinary bureaucrat. Nor was he the sort of ordinary messenger that could be found in every way station in every corner of the empire. For one, on his clothing was embroidered the emblem of the imperial household. He also carried a writ of passage that granted him access to all levels of the government. As though those tokens weren’t enough to establish his authority, his armed escort of fifteen in matching armor spoke volumes about the precious cargo he bore. In a trunk carried by two porters were scrolls addressed to the governors of the Southern Provinces.

He was a eunuch, a servant of the imperial throne. He had entered the emperor’s service as a young man, long years ago. While he never rose to lofty positions in the court like he hoped, he had made a comfortable life for himself among the personal servants of the emperor. Though there were far younger men that were capable of performing this task of delivering these official missives, he insisted on performing this duty himself.

In that sense, he was not unique. Eunuch messengers like him had been dispatched from the capital with the same mission. Each bore the imperial emblem, each carried a precious cargo of scrolls addressed to officials of the empire. Each expected the utmost deference as they delivered their commands, for they were the emperor’s representatives.

His arrival in An’lin was much like the arrival of the others in every part of the empire. First came stares of curiosity at the palanquin that bore him to the official residences of the governor, followed by whispered conversations about the odd manner of dress. This wonder quickly turned to mild panic as officers and guards realized the importance of this messenger. Then came swift trips to the inner sanctuaries of each provincial capital, passing through gardens of serenity and halls of elegance. Each messenger encountered flashes of irritation as a governor protested to being interrupted as they held their own version of court before anger turned to wide-eyed abasement and bowing. Ranked and unranked nobles, scholars, officials stooped deeply as each recognized the significance of the messenger.

In the Governor’s manor in An’lin, the messenger took his time to open the scroll he bore. He didn’t look at the assembled nobles, nor did he look at the governor. Each kowtowed on the ground, their heads touching the floor. He was here to perform a duty. He untied the golden knot, letting the thread dangle. His fingers brushed across the silk backing of the scroll, tracing the patterns of peacock feathers. Grasping the wooden roller on the right of the scroll, he pulled with his left hand, gently unfurling it. The only sound in the room was the breath he took to compose himself.

“To all subjects of the empire,” the messenger began. He swallowed, fighting the rush of emotion. “The imperial sovereign, the son of heaven, the Honghua Emperor, the twelfth emperor of the Xia Dynasty, lord of ten thousand years, peacefully passed away on the eighth morning of the sixth month of the forty-second year of his reign. Let us all join together to mourn the passing of our Emperor and to pray for the peace of his soul. It is now time to unite in loyalty to his successor, the Emperor Tang Wei Qiang, and to continue our efforts to strengthen our nation.”

His final duty complete, he rolled the scroll up and waited for the governor.

“This unworthy governor accepts the emperor’s command. Zunming!”1 The governor said, lifting his head from the ground and kneeling. He brought his hands together in a salute to the messenger and then accepted the scroll, before kowtowing to touch his head to the ground.

“Zunming!” came the answering reply from the others in the room.

* * *

The news spread quickly through An’lin, faster than the formal declarations that came from the governor’s palace. The rumors of the emperor’s death passed from officials to servants. Then they spread beyond the walls of the governor’s manor to private salons of the rich and through the open markets of the An’lin. Vendors and shoppers alike commented on the news. Most were indifferent, though there were many that shook their heads, wondering at the state of the kingdom.

Across the river in He’bian rumors mixed with tall tales and stories of intrigue among the more criminal elements of the city. The emperor was murdered, killed by assassins of the Black Tiger. The emperor died after long years of illness. The emperor had been the victim of an ancient curse. In dark corners of teahouses and inns, some murmured that the Black Tiger General was right—the emperor had indeed lost the Mandate of Heaven and now had lost his life.

* * *

In Dong’shui, the unrest in the city took on a fever pitch. When news of the emperor’s death broke, there were cheers in the streets, celebrations so ecstatic that the officials were unsure of what to do. Fearing for their lives, they retreated within government buildings. Some suspended services for the day, barring their doors until the crowds dispersed.

But they didn’t disperse. As the day wore on, the celebrations turned into protests against the cruelty of the White Crane General and the Northern Army that occupied their city. Emboldened by the cheers of the crowd, brave citizens and refugees spoke up. They did not deserve this fate, they cried. They were faithful to the emperor. They did not warrant cruel punishments or the harsh treatment of the invading soldiers.

From the third-floor balcony of the popular White Bear Inn at the heart of town, three of Magistrate Tao Jun’s staff, Adjutant Ji Ping, Captain Chen, and Officer Ruo, watched the crowds protest grow louder and louder with some concern. They watched the chanting and the shouting, but more importantly, they watched the guards of the city and the soldiers that ruled over them. With Dong’shui’s officials unable to control the crowd, the military took things into their own hands. Soon after, the first protestors fell in a spray of blood, shrieks of horror erupting from the crowd.

Soldiers closed ranks. They brandished their spears, locked shields together, and pushed back against the crowd. The soldiers of the North stood undaunted. After all, they were the fist of the emperor—his will made manifest. They felt nothing towards those they cut down. They knew the truth that their general had taught them: all of these men and women have harbored traitors and rebels. This bloodletting was a sentence richly deserved.

There were those, however, emboldened by the news of the emperor’s death, and enraged by the injustices heaped upon them, that stood against the White Crane’s soldiers. Some managed to swarm the soldiers, dragging them down and pummeling them with rocks, bricks, and other detritus from years of decay in the city. They retrieved the fallen weapons and turned them on the remaining soldiers. For every protestor cut down, three more rose firm in their resolve.

Soon, the tide shifted.

At the edge of the crowd, a Northern Army patrol was completely overwhelmed. Each soldier stripped of their armor, their bodies paraded like the spoils of war.

“This is really bad,” Officer Ruo observed.

“It’s only going to get worse,” Ji Ping muttered.

For once, Captain Chen had no acerbic comeback for his companions. He only nodded in grim agreement.

* * *

After the messenger and his entourage left her quarters at the Temple of Eastern Light, General Peng Hai Rong, the White Crane General, rose to her feet. She unfurled the scroll, reading the text again, her eyes focusing on the seal of the Emperor.

She had in her possession two similar scrolls that bore the same seal. The first was given to her fifteen years ago: her orders to march to the north and extinguish the threat there. It officially named her as ‘She Who Pacifies the North,’ and granted her all the rights and privileges of the Chief General of the Northern Army. On the surface, it was a promotion, but the scroll was a reminder of her humiliation. Exile to the north was her reward for failing to bring the emperor the head of the Black Tiger General, Shazha Kui, and ending his rebellion for good.

The second scroll was a reminder of her redemption. Of course, it was not an official apology—that would be too much to expect from the imperial court, but it was an official summons, a command for her to track down her sworn brother and put an end to his rebellion, and to bring the Black Tiger, alive, to the emperor. A tacit admission of wrongdoing, this scroll was a reminder of the way political winds shift. It was a warning against the politics of the court.

And now a third scroll. While the messenger was here, she felt a flicker of doubt. What if this was a ruse? What if this messenger, this eunuch, wasn’t who he said he was? This was why she unfurled the scroll so quickly after the messenger had left. But the seal fixed upon the document confirmed the truth—this was the real thing.

Not that it would have made a difference, she thought.

“Well, that was certainly interesting,” Commander Yao Rui said. “You can never tell with those eunuchs. They never bring good news.”

“Hmph,” she snorted but smiled at Commander Yao.

Yao Rui had always been a good soldier and, as such, had regarded the world with that pragmatism that comes from being a career warrior. He had no tolerance for the political machinations or the pomp and ceremony of the court. She had given him the choice of remaining in the north to command the troops they left there, but he stayed at her side.

Yao Rui, you fool. You could have done anything you wanted in the Kingdom, and you chose to stay with me. He was well past the usual retirement age for soldiers. There was more grey than black in this close-cropped beard, and when he thought she wasn’t watching, he groaned and muttered about his aching bones.

When this is all over, I’ll make him retire. He deserves it.

She handed the scroll to Commander Yao, who scanned it himself. He arced an eyebrow at the text, giving her a curious look.

“What’s on your mind, Commander?”

“This a broad declaration—the kind that is replicated and posted on every city wall and government building. There isn’t anything specific to us in here.”

“Yes.”

“Then our mission hasn’t changed at all.” Commander Yao rolled up the scroll, struggling with the fine gold thread that kept it closed. He made no apologies for the crude knot he tied. None was needed.

“Exactly.”

“General?” Yao straightened. He placed the scroll on the table at the center of her tent with the map that tracked the movements of their troops and enemy positions.

“Did you not hear the last words of the edict? It is now time to unite in loyalty to his successor and to continue our efforts to strengthen our nation.”

“Empty words.”

“My thoughts exactly.”

“What are your orders?”

“We proceed with our plans. We flush the Black Tiger from his hiding places. We destroy all his safe havens. Keep pressure on the Jingjia valley—threaten but do not destroy it. And then we claim his head as a trophy for the young emperor. If we ignored our orders, we would be no better than them.”

“And what of the reports of the martial sects that have openly denounced our actions?”

“We will pay them a personal visit. It’s time to teach the wulin that they are not above the rule of the imperial throne.”

“Zunming, General.”

Just a while longer, Wei Meng, she promised. A new emperor, but nothing changed. She would bring the southern province to heel. She would stamp out the rebellion and drag the Black Tiger back to the capital.

Just a while longer, Wei Meng.

* * *

In a hidden camp at the base of the mountains, a different sort of messenger brought tidings to the camp of the Black Tiger general. A convoy intercepted. A messenger and his escort slain, their cargo looted.

“So the old man is dead,” Zheng Keyuan said, shaking his head. “The Honghua emperor has finally met his end.”

“It would appear so.”

“I thought it would never happen.”

“He was old when we were young men,” Shazha Kui reminded him.

“There were days I thought he knew the Jade Emperor himself,” Zheng Keyuan joked.

Shazha Kui smiled, the kind a wolf might give after clamping its fangs onto a deer’s neck.

They were silent a moment as they paid respect to the emperor’s memory—a man who had once been worthy of praise and esteem before being led astray by eunuchs. There was a time when the emperor was what the sages would have called a good ruler. He was a man of high integrity and morality. He embodied the virtues of benevolence, justice, propriety, wisdom, and faithfulness. He respected the duty between ruler and ruled—a benevolent ruler.

Those days had long passed.

Somewhere along the way, the emperor he had once known had forgotten his responsibilities to the people, to heed the counsel of the wise, to be true to his station as protector of a kingdom. Complacency gave way to corruption. The rising tide of eunuchs and self-serving ministers drowned out the pleas for genuine help. Conflicts festered across the empire, the people suffered, and heaven withdrew its blessing. It was painfully clear to Shazha Kui that the Emperor had lost the Mandate of Heaven, even if his brothers and sisters in the Order didn’t see it. Poverty in the land. The growing disquiet of the people. The floods and the famines and the lack of preparation against them. All of these were signs that they willfully chose to ignore.

But he could not.

And now the old man was dead.

He had been proven right. His proof was in the heavy-handed way the emperor handled his rebellion—a test the old man failed. The Honghua Emperor could have sent agents to negotiate, a summons to appear in court and Shazha Kui would have answered. Instead, he sent the White Crane General to the south with an invasion force in the thousands—an overreaction, like punishing a child with an executioner’s dao for stealing an apple. He authorized the use of the Soul Fog, leaving thousands dead in its wake, the survivors little better than jiangshi. These were not the actions of the man he once knew.

That man of wisdom and temperance was long gone.

“His son—the crown prince won’t last,” the Protector said.

“A spineless boy will almost certainly be devoured by the imperial court.”

“Chaos will erupt in the court. It won’t be long until it joins the chaos we find here. Soon, all lands will be in chaos.”

“Nothing has changed.” Shazha Kui shook his head. The purpose of the Black Tiger Rebellion was to restore the Mandate of Heaven to the righteous, and wipe the corruption of the old order away. If blood had to be shed for a new era of stability to arise, then that was the course forward.

Nothing had changed.

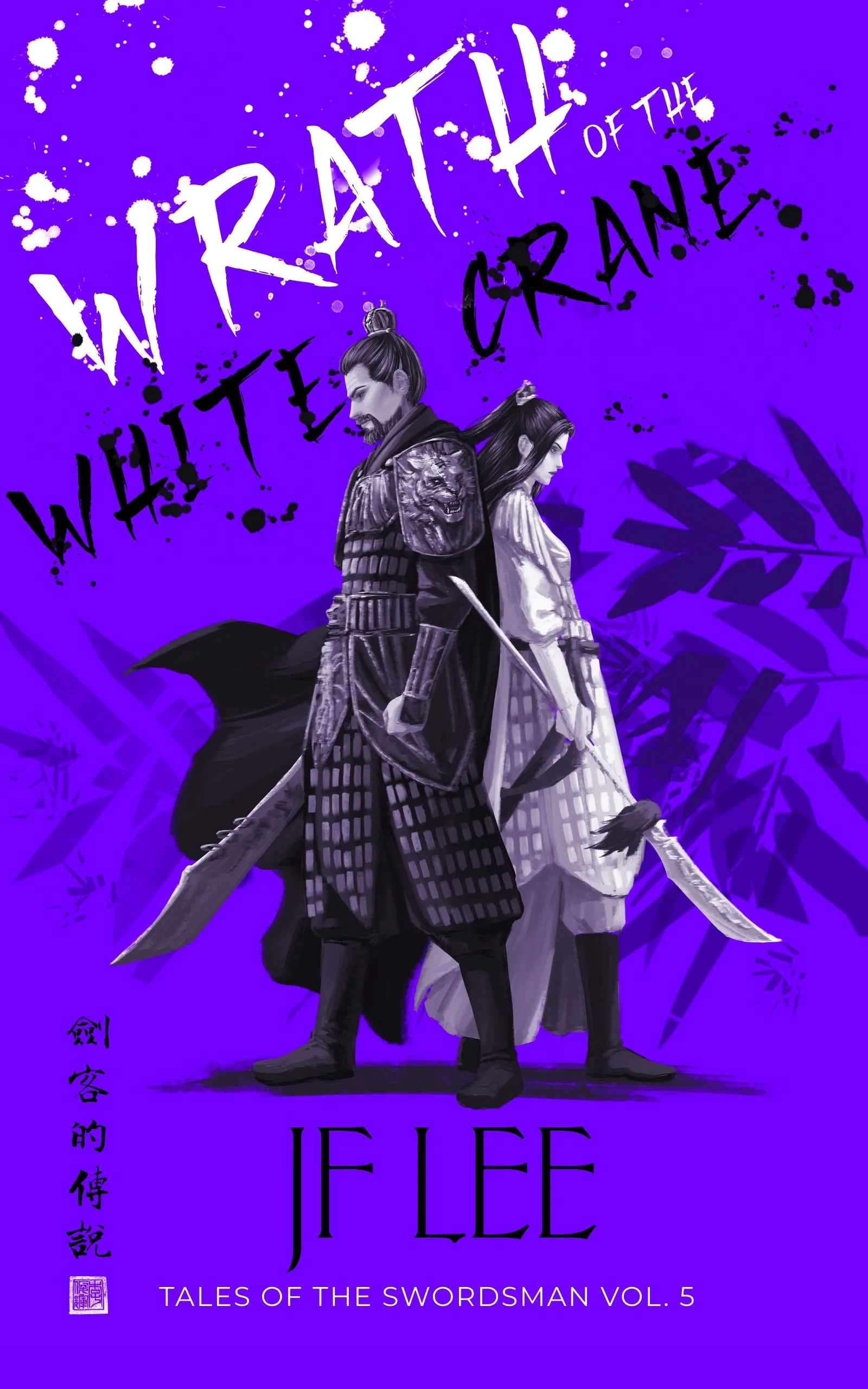

EVERY ACT OF DEFIANCE MUST BE PUNISHED

The Southern Province burns.

The White Crane General’s war against the Black Tiger threatens to consume everything—and everyone—in its path. She will not rest until her nemesis is dead. Her ultimate weapon, the Soul Fog, is a force of annihilation unlike any other, capable of wiping entire cities from the map.

And she will not hesitate to use it.

Shu Yan sets out with her sworn sister to stop this catastrophic weapon. Now armed with her master’s blade, Sorrow, each step takes her deeper into peril as the lines between loyalty and survival blur.

Meanwhile, Li Ming, the last Swordsman of Blue Mountain, seeks a cure for the illness that drains his strength. His journey takes him to a legend, an artifact that could turn the tide of battle.

Yet even as war rages, not all hope is lost. The swordsmen have returned to Blue Mountain and Li Ming is no longer alone. But what can a group of jianke do against the Wrath of the White Crane?