Wuxia vs. Xianxia vs. Western Fantasy: The Ultimate guide (2025)

New to the wuxia genre? Never heard of xianxia? How does this all compare to Western Fantasy? By the end of this guide, you’ll know the difference between the three genres and how they’re all similar.

Table of Contents

Fantasy is where we go when we need an escape from the real world.

It’s always been a mirror of ourselves, our cultures, imaginations, histories, ambitions, and dreams. This is true across all cultures, regardless of origin. While western readers often grow up with stories of knights and paladins, wizards and mages, chosen heroes and epic fights with dragons and kings, eastern audiences are raised with stories of wandering swordsmen, Taoist immortals, legendary martial sects, mythical creatures, and duels of honor and skill.

But you know what they all have in common?

Really cool swords.

Actually, there’s a lot more than just that. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Despite the different cultural traditions fantasy stories come from, they share more in common than not. In recent years, Eastern and Western stories have begun to intersect. Wuxia and Xianxia stories are translated for Western audiences, while stories from authors like Tolkien, Sanderson, and Jemisin are translated for Eastern audiences.

But what exactly is wuxia? How is it different from xianxia? And how does it compare with Western fantasy?

In this ultimate guide, I’ll break down the origins, themes, tropes, and storytelling styles so you’ll know the difference between these genres (and impress your friends). I’ll even throw in some recommendations so you can discover which ones might fit your tastes as a reader.

A pefectly good place to have a duel, if you’re in a wuxia story.

(Source: Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon)

What is Wuxia?

Wuxia Origins in Chinese Literature and History

The word wuxia (武俠) is Chinese in origin. It’s made of two components:

Wu (武) meaning martial.

Xia (俠) meaning heroes.

So what is wuxia? It’s right there on the tin. A story of martial heroes. At its heart, wuxia stories are about ordinary heroes who become extraordinary. This is usually done through martial arts, discipline, and a strong moral code.

Out of our three genres in this ultimate guide, wuxia is the oldest genre with its origins dating back to 2nd or 3rd century BCE. That is OLD. Some of the first wuxia stories originated as far back as the unification (or pacification) of China under the first emperor, Qin Shi Huang. In fact, if you’ve seen the movie HERO, you’ve seen a retelling of one of the oldest wuxia stories in existence.

Throughout Chinese history, stories of wandering heroes (youxia) and assassins were popular tales and legends. The historian Sima Qian makes mention of the exploits of legendary assassins that took on this ‘noble act’ of loyalty and honor. At one point, wuxia stories were considered illegal and seditious. Government officials blamed these tales for growing rebellions, but the genre lived on and thrived.

The history of wuxia is basically a study in Chinese culture. I wrote a brief history of it, detailing some of the cool moments in wuxia history.

Core Themes and Values in Wuxia

The wuxia genre generally follows a few core elements:

The Jianghu (江湖): Literally translating to the ‘rivers and lakes’ of ancient China, this is the setting of all wuxia tales. In a sense, it’s like the lawless ‘wild west’ that’s seen in western movies. It’s less a physical location and more a culture, an underworld and scene for itinerant martial artists, merchants, traders, outlaws, gangs, craftsmen, adventurers, rebels, and more. While the imperial court rules the world, the jianghu rules the underworld. It’s not necessarily a shady place, though there are shady elements. There is a moral code that exists in the jianghu, a set of laws that exists in a world with no laws. For more on the jianghu, check out this guide.

Wugong (武功) or Martial skill: You don’t get a martial hero without martial skill. The heroes of the genre are generally people who rely on training, skill, and discipline rather than magic. They are ordinary people who attain legendary abilities through grounded human effort. How these skills manifest is varied. Our heroes can wield things like swords, spears, fans, hook swords, or even their fists. If you can fight with it (and even if you can’t), odds are there is a martial hero who is a legend with that weapon.

Chivalry or the Code of the Xia: The code of the xia is a chivalrous code that governs the actions of heroes. It is founded on honor and righteousness. It emphasizes repaying acts of kindness, and violence and vengeance on villains. Adherence to this code is what creates heroes and villains, and can create generational grudges and quests that continue for hundreds of years. For more on the code of the xia, check out this guide.

Realism (sort of): While the use of qi can result in some truly remarkable skills and techniques (like pseudo flying across rooftops, and fighting a dozen people at once), wuxia remains grounded in the world of what is considered more realistic. There’s no magic, casting spells, or fighting mythical beasts in this genre.

I want to point out here that the first three points are also found in the Xianxia genre. In many ways, some of the basic settings, concepts, and tropes overlap. Of course, there’s a lot more nuance, which is what we’re going to get to in a moment.

Famous Wuxia Works and Authors

Sound interesting? Check out these authors and stories to experience the genre for yourself.

Jin Yong’s Legend of the Condor Heroes — This is the OG of the modern era of wuxia. Sweeping romances, generational rivalries, long lost martial techniques, and the fate of an entire kingdom. The cultural impact that this series had in Asia is said to be like Lord of the Rings AND Star Wars put together. Wow.

Gu Long’s The Eleventh Son — A contemporary of Jin Yong, this story is a little darker, with a focus on stylish sword work and assassins. Romance, revenge, and a legendary sword.

Classic films: wuxia is a genre to be experienced visually. Some of my personal favorites include: Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, Hero, Shadow, House of Flying Daggers, A Touch of Zen, Once Upon a Time in China, and so many more. I always revisit these movies when I need inspiration.

JF Lee’s Tales of the Swordsman — Revenge is a dish best served with dumplings. Li Ming, the last swordsman of Blue Mountain, has been on the cold trail of his master's killer for the last fifteen years. With no new leads, his search has become increasingly more futile...at least until he meets young Shu Yan, a spunky runaway from the pleasure houses. With the help of a ragtag group of heroes like a corrupt magistrate, a fearless spearwoman, a merchant princess, an icy assassin, and a cook's wife turned crime boss, they'll find the fate of an empire tangled in what was supposed to be a simple quest for revenge.

You definitely should check out that last one. I promise it’s worth your time.

What is Xianxia?

Xianxia (仙俠) literally means immortal heroes. As a genre, it evolved from wuxia, sharing similar settings and themes. But where wuxia is grounded in realism, xianxia is a fantasy mix of Taoist philosophy, alchemy, and myth. While our heroes in xianxia wander around righting wrongs and doing other hero things, these heroes are also primarily concerned with attaining immortality through the cultivation and refining of their qi. This has resulted in this genre being commonly referred to as the cultivation genre.

This genre is essentially Eastern fantasy because it incorporates many mythical elements as well. Take the tropes of wuxia, add in a few gods, monsters, demons, dragons (!), etc., and it becomes xianxia.

Perhaps one of the most famous (and oldest) examples of this genre is Journey to the West, or the story of the Monkey King, Sun Wukong. If this genre starts to sound familiar, it should. You will find many elements of this genre in shonen manga and anime. After all, Dragon Ball once started as a retelling of the Monkey King’s adventure.

Taoism, Immortality, and Qi Cultivation

Taoism is the foundational belief/spiritual framework for the xianxia genre. Taoism seeks to find harmony with the tao (the way), understand the balance between Yin and Yang, and cultivate qi (life energy). Traditionally, this belief has led to practices like tai chi, meditation, and medicines that improve life.

Xianxia focuses on the beliefs of Taoism and takes it to the next level. The protagonists believe that through Taoist ways like cultivation, medicinal skills, and the practice of martial arts, they can become immortal. It’s a beautiful concept that should resonate with modern audiences. In this case, through hard work, our heroes can become gods.

The quest for immortality is at the heart of every xianxia story, and the journey to transcend the mortal world and live in the heavenly realm with other gods and people that have ascended is the main point. Along the way, they might pick up a magical artifact, meet gods and demons, and split a mountain or two.

Key Xianxia Tropes and World Building

Cultivation and the quest for immortality: This is it. Characters refine their qi so that they can transcend mortality and become immortal gods. Think of cultivation as an Eastern magic system and you’ve got it.

The jianghu on magic: Take the jianghu from the previous section, add in a dash of magical, and you’ve got a xianxia setting.

Unbelievable powers: If the wuxia genre was grounded in ‘mortal’ abilities, then xianxia heroes have powers that rival gods. Flight, teleportation, manipulation of elements are almost commonplace. Astral projections, shattering of reality, martial techniques that destroy entire landmasses are par. If you like incredible, OP abilities, this is the place to go.

The young disciple’s journey: Often the main character of a xianxia series starts as a nobody and through hard work and discipline, comes to dominate the entire world.

Tribulations: Becoming a god isn’t easy. Protagonists often have to break into new realms by experiencing heavenly ‘ordeals’ to level up. These are often tests that prevent mortals from gaining too much power or challenging natural laws. It’s a pass fail test. Pass, and you attain the next level in cultivation. Fail and you’re fried by lightning.

Magical artifacts, alchemy and pills: no journey is complete without cool magical stuff. Expect magical weapons, cauldrons that refine souls, talismans that control elements, elixirs and pills that boost cultivation and more.

Complex social hierarchies: Clans, sects, empires, kingdoms? How about the different tiers of heaven and hell? Did you know that gods and demons have bureaucrats? You can never escape red tape. Don’t even try.

Popular Xianxia Stories and Authors

Oh man, this is a hot area of fantasy right now. Get ready for a whole lot of good recommendations. Many of these series have been adapted into manhua (comic) and donghua (animated) formats, too.

Coiling Dragon by I Eat Tomatoes – empires rise and fall, Spells, swords, and immortal beings of unimaginable power. A clan in disgrace rises from the ashes. A new hero reclaims the lost glory of his clan and becomes a new legend.

I Shall Seal the Heavens by Er Gen — A young scholar forced into a cultivator sect tries to do good in a world that preys on the weak. Both comedic and dramatic, this series is a classic.

Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation by Mo Xiang Tong Xiu (MXTX) — Two parallel tales recounting past and present lives. Forced reincarnation with forbidden methods. A love story with a rabid fanbase devoted to the lead same-sex couple. It’s been adapted as a live-action series, The Untamed.

A Thousand Li by Tao Wong — A cultivation series that follows the life of a farmer and his journey to immortality. This series spans 12 books and is ongoing.

What is Western Fantasy?

Ahhh, western fantasy. The fantasy genre ranges from ancient myths to epic sagas. Magic and magical creatures are the norm. It often draws from myth and folklore, and sometimes combines our contemporary world with the fantastical. It’s literally everywhere. We see it in media, film, television, graphic novels, animation, video games, and just about every avenue of entertainment. It’s unlikely you’re unfamiliar with this genre, unless you’ve been hiding in a cave somewhere. But that’s ok, this guide is friendly to cave-dwelling hermits.

If you’re curious how some of these traditions collide with eastern fantasy, then check out my Tales of the Swordsman series that combines wuxia heroism with epic scope.

European Myth and Epic Foundations

When we talk about western fantasy, we typically talk about fantasy and myth traditions that originate in European cultures. They may feature fae and elves, orcs, dragons, vampires, and other creatures. Stories may contain elements from Christian, Arthurian, Norse, Greco-Roman, and other European legends.

While myths and legends have always been a part of society, it wasn’t until the advent of high fantasy, especially works like J.R.R. Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings, C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia, and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea, helped popularize what we call the fantasy genre today.

Core Elements of Western Fantasy

Medieval Aesthetic: Castles, knights, kings and queens, princes and princesses, sprawling kingdoms, horses and farmlands, quaint villages, and more. You’ve seen it all before. If the jianghu is the basic setting of a wuxia/xianxia fantasy, then this medieval setting is the home turf of western fantasy. Think Dungeons and Dragons.

Magic Systems: Magic is a central part of any fantasy world. Whether the magic system has hard rules like Brandon Sanderson’s worlds, or its understated like in Middle-earth, magic plays a key role in a western fantasy.

Races and creatures: Elves, dwarves, orcs, dragons, cat folk, merpeople, and more! The genre often features diverse non-human races. They tend to fall into certain tropes and archetypes too. Elves are arrogant and ancient people. Dwarves are stubborn underground dwelling folk (and somehow always have a Scottish accent), and Orcs are brutes.

The Epic Quest of Good vs Evil: There’s always an epic quest that involves the fate of an entire world. Go defeat the dark lord. Recover or destroy the magical artifact. Rescue the princess. Slay the dragon. Participate in a rebellion that tears down the evil rule of a king. You know the drill. At the heart of western fantasy is the battle of good vs evil. There is morality, power, love and hate, all framed within a medieval lens.

Modern Western Fantasy Icons

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkein — the OG high fantasy series of the modern fantasy era. I don’t think I really need to say much about this epic, other than you should read it (or at the very least watch the movies).

Game of Thrones by George R.R. Martin — Take the high fantasy but make it gritty. If you’re looking for an ending to the epic tale, keep waiting. Fans have been waiting for more than 30 years for this series to end.

The Stormlight Archives by Brandon Sanderson — Intricate world-building, epic scope, and unique magic. These are hefty books with complex storylines.

The Wheel of Time by Robert Jordan — An epic series that is set in a world where time is cyclical. It features the reincarnation of characters from a distant age, including one responsible for breaking the world. Even though this is a Western fantasy, there are some elements of the story that are distinctly Eastern.

The Broken Earth Trilogy by N.K. Jemisin — Set in a fantasy world where seasons are apocalyptic events that can last for generations, the central plot follows a mother in search of her kidnapped daughter.

Comparing Wuxia, Xianxia, and Western Fantasy

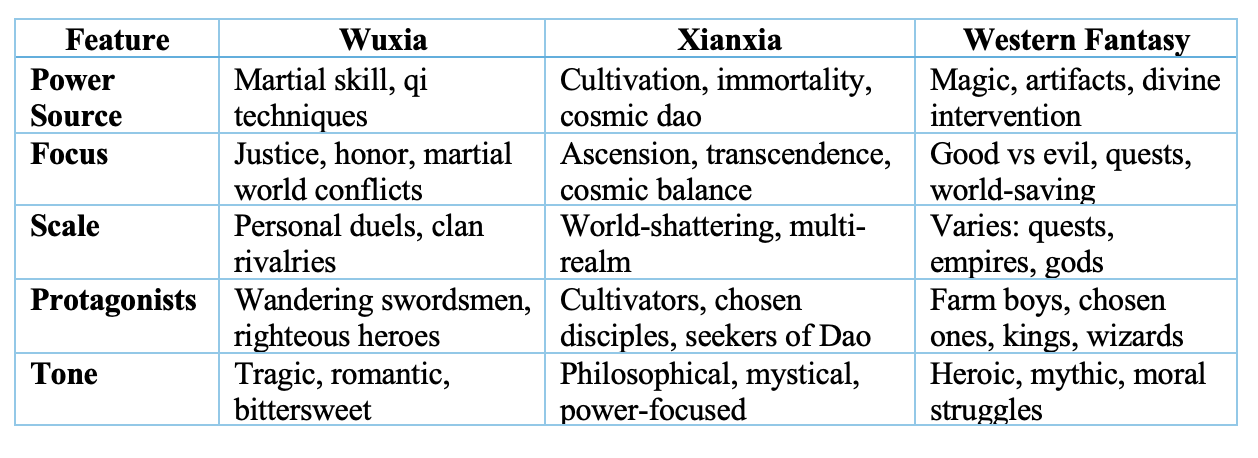

If you’ve been following along, by now you should realize that there’s actually a lot in common between these genres. But for a quick reference, here’s a chart of the differences and similarities between the genres.

The Difference in Worldview, Cultural Roots, and Philosophy

As you might suspect from storytelling styles from eastern and western cultures, the religions and philosophies of their respective backgrounds. You really can’t escape philosophy in fantasy—it’s an ingrained part of the genre, and in some ways an essential part of the setting. This creates very different storytelling flavors:

Wuxia: Justice within human society.

Xianxia: Transcendence beyond human society.

Western Fantasy: Heroism against evil in the world.

Wuxia and Xianxia are byproducts of Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist traditions. While each of these schools of thought are distinct, it’s important to note that over the thousands of years these philosophies have co-existed, many of these ideas have blended together. Principles of righteousness, harmony, and enlightenment are some of the most important themes—a solid morality.

There is a strong sense of self-improvement in these stories, whether it’s through cultivation to increase a character’s ‘power level,’ a martial improvement to increase a skill with a technique, or an intellectual and spiritual enlightenment. It’s an old trope, but the genres are rife with retired martial heroes, masters that have reached a certain level of skill and have put down their weapons and retreated from the world. Often this is because of a spiritual enlightenment that has caused them to abandon the martial way. This is especially true in the wuxia genre. Societies in wuxia and xianxia stories tend to follow traditional Confucian/imperial hierarchies, with their accompanying models of respect and honor.

Xianxia stories, in particular, lean more heavily toward Daoist and Buddhist traditions. And because these stories extend beyond ‘the mortal realm,’ there is an emphasis on reincarnation, the cycle of rebirth and death, and karma. Because of reincarnation, the problems of one life can come back in the next life and the one after that.

Western Fantasy, on the other hand, tends to draw on the philosophic and religious background of Europe. Norse, Christian, and Greco-Roman myths emphasize the struggle of good against evil. Some of these stories are allegorical, using their fictional world to explore human morality.

Common Tropes and Conventions in Wuxia, Xianxia, and Western Fantasy

Common Wuxia Tropes:

Martial arts: There is a reason why these are martial hero stories. You cannot have a wuxia story without martial arts. Related to this means training sequences, secret manuals containing powerful techniques. Characters often cultivate their qi, or strike at pressure points to disrupt the flow of a person’s qi. With enough skill, characters can also use qinggong, the skill that lets them pull off acrobatic feats.

Clans or sects: While there are heroes that train on their own, most belong to a clan or a sect whose martial tradition is passed down from generation to generation. Often there are rivals and frenemies, betrayals and double crosses. Nothing ever goes completely smoothly in a martial sect.

The code of the xia: The code of conduct that governs the martial world, this code is an unofficial one, though it is one that leads heroes to seek revenge and right wrongs.

Legendary weapons: Oh my gosh, the weapons in wuxia are always so cool. Legendary swords? Rope darts? Meteor hammers? Maces? Spears? Boat oars? Weighing scales? If it can be used to fight, it’s a wuxia weapon.

Common Xianxia Tropes:

Need more power: It’s one thing to cultivate your qi to become a martial hero. It’s another thing completely to cultivate your qi to become an immortal. Power levels are endless in xianxia, and it’s never enough for a character to just become an immortal.

Cultivation bottlenecks: The heroes of the genre ultimately plateau and come to a bottleneck, a place where they can no longer progress. If you’re not progressing in this genre, then you’re dead, and so the heroes work hard, train, and fight to break through to the ‘next’ level. This tension is a popular theme.

Heavenly tribulations: Often a powerful lightning storm, these are trials sent by the will of heaven or the dao to test a cultivator. Heroes must endure these trials to reach higher stages of power.

Cool weapons: Ok, hear me out. How about RIDING a giant flying sword like a surfboard? Yes. That’s a thing.

Common Western Fantasy Tropes:

The Chosen One: The chosen one of whatever prophecy (or not). Whatever the case is, the hero of the story is special, and has some kind of special fate about them. Whether they accept the call of the quest or not is entirely up to the whims of the story.

Dark lords: The chosen one has to battle someone, and often that’s the evil dark lord and their shadowy armies.

Found Families: You can’t have a chosen one without their scrappy group of allies. You can’t defeat the dark lord and save the world unless you have friends, family, and allies. Sometimes they’re all one and the same thing.

Good vs. Evil: The central conflict of many stories. And yes, it’s not specific to just Western fantasy.

There are a ton of tropes that cross over between genres, and to be honest, a list of all the tropes would take a long time to read through. Obviously, there are found families in all genres, and there are dark lords and demons and monsters everywhere—which leads us to the next section.

East Meets West: Blended Stories, Cultural Impacts and Crossovers

No culture holds a monopoly on ideas. Each genre reflects the culture they come from, but the themes that each espouse are not singular. They are universal ideas that find relevance in all forms of literature. Together they show how different cultures dream of power, destiny and the limits of human will and imagination.

The best part of this era that we live in is all the crossover and blending of stories we see. There are tropes that occur in western fantasy that are appearing in eastern stuff, and vice versa. It’s common to see a fantasy world with a magical system that’s grounded in stuff like cultivation. Likewise there are cultivation systems that involve magic and fantasy races like elves and orcs. In fact, the ‘leveling up’ found in xianxia, is a very popular idea that finds commonalities in our video game experiences and the LitRPG genre.

We are in a time where people are interested in other cultures. What were once stories that were confined to Chinese are now translated into English and other languages. Audiences around the world are being exposed to wuxia and xianxia through all forms of media. With growing interests in K and C dramas, these genres are ripe for hybridity. It’s not just stories that are getting blended together, we are seeing cultures mix in new and exciting ways.

Hybrids are considered new species, and I love the idea of new subgenres emerging from these fantasy genres. They’re not a mechanical sum of existing cultures, but rather a ‘remix’ a new version of music, art, fashion, stories, and even food. Audience tastes are growing more diverse, and we are all a mash up of competing fandoms (you can like Star Wars and Star Trek, just like you can like both Marvel and DC).

One reviewer once described the first book in my Tales of the Swordsman series, Sword of Sorrow, Blade of Joy, as a “Chinese version of Samurai Champloo.” To this day, that’s still one of the best compliments I’ve ever received. Champloo, for me, is the gold standard of cultural fusion. On the surface, it’s a familiar tale—young girl saves a ronin and a pirate and convinces them to help her on her quest. But what makes the story so brilliant is the way it integrates hip hop culture into the setting. The opening credits are kanji brushstrokes and turntable swagger. Episodes dive into graffiti wars, freestyle battles, and katana wielding b-boys.

It's a fine example of how cultures are blending.

Ya Boy Kongming! takes a similar approach, though in a wildly different direction. This series leans on the isekai trope of “second life,” but instead of another teenage power fantasy, it drops Zhuge Liang—the greatest strategist of the Three Kingdoms era—into modern Shibuya. From there, it gleefully blends Chinese history, Japanese idol culture, and hip hop. And yes: at one point, the ancient tactician himself throws down in a rap battle. It’s ridiculous, it’s brilliant, and it works.

The Wuxia Hybrid — The Tales of the Swordsman

The wuxia hybrid is how I appeal to my audiences in the Tales of the Swordsman series. I emphasize familiar tropes to the genre (legendary swords, wandering swordsmen, revenge, honor) and use an episodic style of interconnected stories that feel like binge watching episodes of a show. As the books in the series progress, these stories draw in more classic wuxia tropes—training a new disciple, the search for a lost manual, avenging a fallen friend, and of course, a found family.

With that as the starting point, that’s when I start having fun. I add cultural footnotes that explain language nuances and break the fourth wall with jokes. I reference pop culture by paying homage to shows like Avatar: The Last Air Bender, Star Wars, and artists like BTS. I combine humor with tragedy for an experience that’s both familiar and new.

Sound interesting? Check out the series here.

The future of fantasy is global and hybrid. Stories were never meant to exist in a vacuum. I expect that over the next few years these genres will blend together even more than they are now.

THE TALE OF THE SWORDSMAN BEGINS

The adventure of Li Ming and Shu Yan was NOT the story I wanted to tell. Back then, I was working on a sweeping generational epic that was going to see the fall of a dynasty and the rise of a family of warlords — siblings pitted against each other in the aftermath of the fall of an empire.

But after about 30,000 words, I needed a break. So one afternoon on a July in 2019, I set out to write a short story — one that had been bouncing around in my head for a while.

RUNAWAY is the short story that came out of that weekend. After writing it, I was surprised by how fun it was. These two characters seemed to have a lot to say. Would it really be so bad to take a break from the epic and write their adventures a bit more?

By the beginning of 2020, I had three of these little tales. And then the pandemic hit and I lost all of my clients. I suddenly had a bit of extra time, and I knew I was going to hate myself if I didn’t take the chance to work on the Tale of the Swordsman (after all, the pandemic was only going to last a few months right? How naive I was back then).

Before I knew it, I had a whole novel.

And the adventures of Li Ming and Shu Yan were just beginning.